The Silent Struggle: Navigating the World of Dry Eyes in the Digital Age

In our increasingly digital world, where screens dominate both our professional and personal lives, a silent epidemic is on the rise: dry eye syndrome. This condition, often overlooked and underestimated, affects millions of people worldwide, causing discomfort, visual disturbances, and a significant impact on quality of life. In this comprehensive exploration, we’ll delve into the causes, symptoms, and treatments of dry eyes, shedding light on this common yet often misunderstood condition.

Understanding Dry Eye Syndrome

Dry eye syndrome, also known as keratoconjunctivitis sicca, is a multifactorial disease characterized by a lack of proper lubrication on the eye’s surface. This condition occurs when the eyes don’t produce enough tears or when the tears evaporate too quickly (Stapleton et al., 2017). The result is a range of uncomfortable symptoms that can significantly affect daily activities and overall well-being.

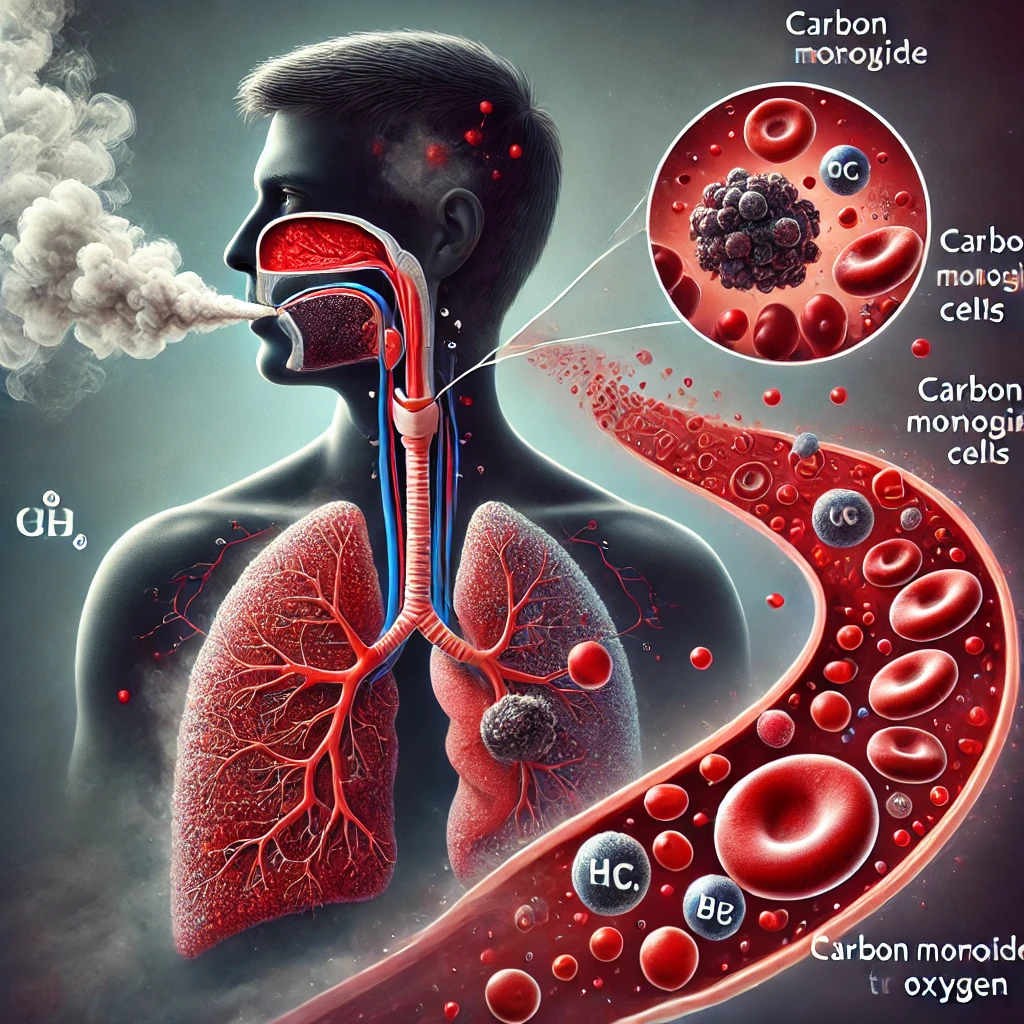

The Anatomy of Tears

To understand dry eyes, it’s crucial to first grasp the importance of tears. Tears are more than just a response to emotions; they play a vital role in maintaining eye health. The tear film consists of three layers:

- Lipid layer: The outermost layer that prevents evaporation

- Aqueous layer: The middle layer that provides moisture and nutrients

- Mucin layer: The innermost layer that helps the tear film adhere to the eye’s surface

When any of these layers are compromised, it can lead to dry eye symptoms (Willcox et al., 2017).

Causes of Dry Eyes

The etiology of dry eye syndrome is complex and multifaceted. Some common causes include:

- Age: As we get older, tear production naturally decreases (Sharma & Hindman, 2014).

- Environmental factors: Low humidity, wind, and air conditioning can accelerate tear evaporation (Wolkoff et al., 2012).

- Digital device use: Prolonged screen time reduces blink rate, leading to increased tear evaporation (Portello et al., 2013).

- Medications: Certain drugs, including antihistamines and antidepressants, can reduce tear production (Fraunfelder et al., 2012).

- Medical conditions: Autoimmune diseases like Sjögren’s syndrome can affect tear production (Brito-Zerón et al., 2016).

- Hormonal changes: Menopause and hormonal imbalances can contribute to dry eyes (Sullivan et al., 2017).

- Contact lens wear: Long-term use of contact lenses can lead to dry eye symptoms (Dumbleton et al., 2013).

Recognizing the Symptoms of Dry Eyes

Dry eye syndrome can manifest in various ways, and symptoms may fluctuate throughout the day. Common signs and symptoms include:

- Burning or stinging sensation in the eyes

- Feeling of grittiness or foreign body sensation

- Redness and irritation

- Blurred vision that improves with blinking

- Light sensitivity

- Difficulty wearing contact lenses

- Watery eyes (paradoxical tearing)

- Eye fatigue and discomfort during screen use

It’s important to note that symptoms can range from mild to severe, and their impact on quality of life should not be underestimated (Stapleton et al., 2017).

Diagnosis and Assessment of Dry Eyes

Diagnosing dry eye syndrome involves a comprehensive eye examination and may include several tests:

- Tear break-up time (TBUT): Measures how quickly the tear film evaporates

- Schirmer test: Quantifies tear production

- Ocular surface staining: Reveals areas of damage on the cornea and conjunctiva

- Meibomian gland evaluation: Assesses the function of oil-producing glands

Additionally, questionnaires like the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) help evaluate the impact of symptoms on daily life (Wolffsohn et al., 2017).

Treatment Options

Managing dry eye syndrome often requires a multifaceted approach tailored to the individual’s specific needs. Treatment options include:

- Artificial tears: Over-the-counter lubricating eye drops can provide temporary relief (Jones et al., 2017).

- Lifestyle modifications: Increasing humidity, taking regular screen breaks, and staying hydrated can help (Wolkoff et al., 2012).

- Prescription medications: Drugs like cyclosporine and lifitegrast can increase tear production (Pflugfelder et al., 2014).

- Punctal plugs: Small devices inserted into tear ducts to prevent drainage and retain tears (Marcet et al., 2015).

- Intense Pulsed Light (IPL) therapy: A newer treatment that may improve meibomian gland function (Craig et al., 2015).

- Omega-3 fatty acid supplements: May help improve tear film quality (Epitropoulos et al., 2016).

- Autologous serum eye drops: Made from the patient’s own blood, these can be beneficial in severe cases (Semeraro et al., 2014).

The Digital Age and Dry Eyes

As our lives become increasingly intertwined with digital devices, the prevalence of dry eye syndrome is on the rise. The phenomenon known as “digital eye strain” or “computer vision syndrome” is closely linked to dry eye symptoms (Portello et al., 2013). When we focus on screens, our blink rate significantly decreases, leading to increased tear evaporation and eye strain.

To combat this, eye care professionals recommend the “20-20-20 rule”: Every 20 minutes, take a 20-second break and look at something 20 feet away. This simple practice can help reduce eye strain and promote more frequent blinking (Sheppard & Wolffsohn, 2018).

The Impact on Quality of Life

While often considered a mere nuisance, dry eye syndrome can have a profound impact on quality of life. Studies have shown that severe dry eye symptoms can be as debilitating as angina or dialysis in terms of impact on daily activities and mental health (Schiffman et al., 2003). It can affect work productivity, social interactions, and even lead to depression and anxiety.

Understanding this impact is crucial for both patients and healthcare providers in addressing the condition holistically and providing appropriate support and treatment.

The Future of Dry Eye Management

Research in dry eye syndrome is ongoing, with promising developments on the horizon:

- Nanotechnology: Nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems may provide more targeted and effective treatments (Baudouin et al., 2017).

- Stem cell therapy: Shows potential for regenerating damaged ocular surface tissues (Ljubimov & Saghizadeh, 2015).

- Neurostimulation devices: May help stimulate natural tear production (Friedman et al., 2016).

- Personalized medicine: Genetic and biomarker analysis could lead to more tailored treatment approaches (Sullivan et al., 2017).

Dry eye syndrome, while common, is far from a trivial concern. As we navigate an increasingly digital world, understanding and addressing this condition becomes ever more crucial. By recognizing the symptoms, seeking appropriate diagnosis, and exploring the range of available treatments, those affected by dry eyes can find relief and improve their quality of life.

Remember, your eyes are precious, and taking care of them is an investment in your overall well-being. If you’re experiencing persistent dry eye symptoms, don’t hesitate to consult an eye care professional. With the right approach, you can keep your eyes comfortable, healthy, and ready to take on the visual demands of our modern world.

Written by : Farokh Shabbir

References

Baudouin, C., et al. (2017). Frontiers in Pharmacology, 8, 168.

Brito-Zerón, P., et al. (2016). Nature Reviews Rheumatology, 12(9), 535-547.

Craig, J. P., et al. (2015). Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 56(3), 1965-1970.

Dumbleton, K., et al. (2013). Optometry and Vision Science, 90(7), 637-649.

Epitropoulos, A. T., et al. (2016). Cornea, 35(9), 1185-1191.

Fraunfelder, F. T., et al. (2012). Drugs of Today, 48(2), 155-171.

Friedman, N. J., et al. (2016). American Journal of Ophthalmology, 165, 97-104.

Jones, L., et al. (2017). The Ocular Surface, 15(3), 575-628.

Ljubimov, A. V., & Saghizadeh, M. (2015). Progress in Retinal and Eye Research, 49, 17-45.

Marcet, M. M., et al. (2015). Clinical Ophthalmology, 9, 1419-1425.

Pflugfelder, S. C., et al. (2014). American Journal of Ophthalmology, 157(6), 1282-1289.

Portello, J. K., et al. (2013). Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics, 33(3), 230-237.

Schiffman, R. M., et al. (2003). Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 1(1), 41.

Semeraro, F., et al. (2014). BioMed Research International, 2014, 467136.

Sharma, A., & Hindman, H. B. (2014). Clinical Ophthalmology, 8, 1573-1581.

Sheppard, A. L., & Wolffsohn, J. S. (2018). Clinical and Experimental Optometry, 101(3), 329-336.

Stapleton, F., et al. (2017). The Ocular Surface, 15(3), 334-365.

Sullivan, D. A., et al. (2017). The Ocular Surface, 15(3), 284-333.

Willcox, M. D., et al. (2017). The Ocular Surface, 15(3), 366-403.

Wolkoff, P., et al. (2012). Environment International, 44, 100-111.

Wolffsohn, J. S., et al. (2017). The Ocular Surface, 15(3), 539-574.